Photographers have been reimagining the American West ever since cameras were ferried across the Mississippi River in the 1850s; photographs being the primary way people in the East could see what wonders lay in the then uncharted and mythical territories far to the West of the “Great River.” According to the Native Languages of Americas website, “Misiziibi” is the native name of the river in the Ojibwe language.

Since the 1860s when the first photographs of Yosemite Valley were made, photographs—both still and moving images—have been instrumental in promoting the West as an unexplored wilderness and the land of opportunity. Although unacknowledged when convenient, as it often was, the lands west of the Mississippi were traditional homelands to many First Peoples and a diverse cross-section of Hispanic peoples who moved into the land with the Spanish Friars and Conquistadors funded by the Spanish Crown long before the West was Anglicized.

In the past few decades, a growing number of photographers have challenged the romantic myth of the American West to reflect the cultural, environmental, and racial complexities of our shared histories more accurately in an on-going conversation about what it means to be an American, how identity and the landscape are intertwined and what the real West looks like today.

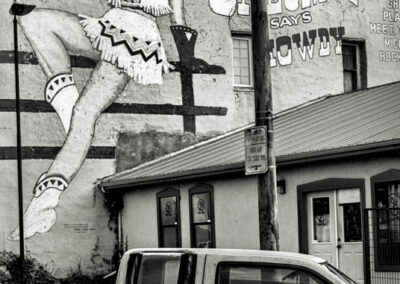

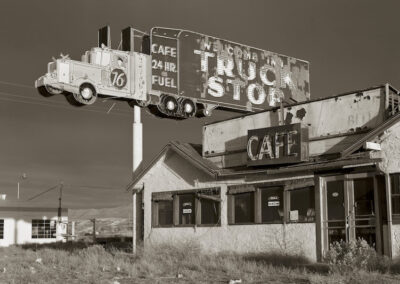

Photographers Joan Myers and Steve Fitch have both lived in the West for most of their lives. They document the changing landscapes of which they are a part; their lives intimately intertwined with the history of the arid lands they call home. Their images capture landscapes made famous in countless Western narratives of both literature and film, but they move in closer with their lenses to reflect the details often overlooked in a sweeping landscape narrative, gently critiquing the myth of the oversized cowboy with his long gun, the absurdity of the oversized teepee selling espresso, the oversized sombrero, the seedy roadside hotels bedazzled with garish flashing neon, the derelict movie theaters and drive-ins hawking a fading American Dream.

Both artists expose the cracks of co-opting other cultures to romanticize a fabricated fable when the truth is harsher. They invite their viewers to pull back the veil and unpack the complicated narratives exposed in the landscapes they reveal with a clear-eyed mixture of love and regret.

– Mary Anne Redding, Exhibition Curator

Clockwise from top right: Steve Fitch: Mural in Dimmit, Texas, 2012; Steve Fitch: Motel, Highway 66,Elk City, OK, 1973; Joan Myers: Amado, TX, 2016; Joan Myers: Monument Valley, UT, 2021

Artist statement

For more than forty years, I have made road trips through the small towns and back roads of the American West. I’ve photographed on some of the least traveled roads in the country, sometimes with purpose, more often with curiosity guiding my path. I’ve stopped at local cafes in small towns for lunch or dinner and spent the night in family-run motels. I’ve wandered the Native American reservations. Along the way, I’ve met folks from all walks of life and enjoyed their good humor and strong sense of community. As I traveled, I explored the rural West visually, photographing landscape, portraits, iconography and street life.

Over the decades, I have seen daily life in rural America change. Many jobs have been downsized or lost, and with them the belief in American ideals of open space, economic well-being and unlimited options. It is a struggle to keep food on the table and to afford child and health care. It is often no longer possible to earn a decent living and support a family, much less find a good doctor or a decent grocery store in the hometown where one’s parents settled decades earlier.

The story of the rural West has been historically seen as Our Story, the American Story. But the American Dream has become more difficult to grasp and more problematic to define. A new myth for our country, comparable to that of the western hero, is yet to evolve, and perhaps one never will. It would have to be one that depends less on the macho cowboy symbology of the American West, one that is more expansive, more inclusive, more befitting a country founded on sweeping democratic ideals.

We don’t know yet which images and metaphors will define America in the twenty-first century–a time of cultural realignment, technological change, and the terrifying consequences of environmental degradation and global warming. What is certain is that the imagery depicted in this exhibition is rapidly disappearing.

– Joan Myers, Santa Fe, 2021

I attended a new elementary school in the 1950s that was built on an old Pomo Indian campground in Ukiah, California. For the first couple of years the kids— including myself—found and collected arrowheads. I wondered then what a collection of artifacts could tell me about a culture, about what gets made and what gets left behind. Later in high school and then in college I began using photography as a tool to explore that question.

A good way to engage with my photographs might be to think of an arrow. A lit-up neon arrow with its beautiful glow is in many of my nighttime highway photographs and it seems a suitable metaphor for how I use photography. The first night photograph I made, in 1972, was of a motel with a neon clock visible through a window, “Motel, Highway 85, Deadwood, South Dakota, 1972.” I love how the clock shows what time the photograph was made (8:46 PM) and how long the exposure took—about a half second according to the blurred second hand on the clock. By making that photograph I was sharing something I discovered along the highway and felt was significant—as if wielding an arrow, I pointed to it with my camera.

Photography has also been useful to me in the way that it can “collect and compare” by assembling examples of subjects scattered through the landscape. In my composite, Motel Signs, 1979 to 1989,” there are twelve photographs of motel signs from twelve different towns. The signs were photographed over a ten-year period; in the assemblage, they are collected and displayed together so that comparisons can be made between them– for example, how one sign says “television” and another “TV” or one says “air-conditioned” and another “cooled by refrigeration.” Such distinctions say something about the changes in our culture over time.

Signs are also like arrows; they give us information that points us in a direction. In my photograph, “Billboard, Highway 180, Grand Canyon, Arizona, 1972,” the message is clear: “FILM: HIT the RIM LOADED,” i.e., be prepared so that you can make that important photograph when the time comes. Ever since making that photograph, I have made pictures—first in black and white, later in color—that arise from this challenge and speak to the strange beauty of change and loss along the roadside and in other hidden places in the West.

The photographs taken inside abandoned buildings on the high Great Plains that are in my book, Gone, tell stories about lost worlds and lives that have been left behind. In the photograph, “Gymnasium in a WPA-built school in Wheatland, Eastern New Mexico, July 17, 1992,” there is a constellation of sunlight blotches cast from holes in the ceiling that are projected throughout the space. The walls are made from sandstone quarried from the nearby caprock formation. There are fossils in the sandstone, and on blackboards in some of the former classrooms there remain chalk messages put there on the last day of classes before the school closed, thirty years before I made this image. In these photographs the lost worlds of interior spaces are packed with artifacts: clocks and calendars, paintings of cowboys and musical notes, clothes, dishes, furniture, and, saddest of all, family photographs—all left behind. These artifacts tell a sad, albeit beautiful, story about survival in the difficult and ever-changing landscape of the High Plains.

– Steve Fitch, Santa Fe, 2021

About the artist

Joan Myers

Joan Myers has been taking photographs for more than forty years, exploring the relationships between people and the land. Myers turned to photography during the early 1970s as her life’s work. Her photographs have since appeared in more than fifty solo and eighty group exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe including three Smithsonian exhibitions.

Her images are in the permanent collections of the Amon Carter Museum, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Center for Creative Photography, Denver Art Museum, George Eastman House, High Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Nevada Museum of Art, and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others.

Her award-winning books include Fire and Ice: Timescapes (Damaiani, 2016), The Jungle at the Door: A Glimpse of Wild India (George F. Thompson, 2012), Wondrous Cold: An Antarctic Journey (Smithsonian Books/HarperCollins 2006), Salt Dreams: Land and Water in Low-Down California (New Mexico 1999), Pie Town Woman (New Mexico, 2001), Whispered Silences: Japanese Americans and World War II (Washington, 1996), Santiago: Saint of Two Worlds (New Mexico, 1991) and Along the Santa Fe Trail (New Mexico, 1986). Her current work centers on the American West. Myers maintains her studio and residence near Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Steve Fitch

After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley with a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology in 1971, Steve Fitch worked for five years photographing along America’s two-lane highways. In 1976, the photographs were published in a book entitled, Diesels and Dinosaurs: Photographs from the American Highway. After completing his master’s degree in Fine Art Photography from the University of New Mexico in 1878, Fitch worked on several other projects. His photographs have been widely exhibited and collected as well a published in a number of books including Marks in Place: Contemporary Responses to Rock Art (1988), Gone: Photographs of Abandonment on the High Plains (2003), An Island in the Sky: Llano Estacado (2011), Motel Signs (2011), American Motel Signs, 1980 to 2008 (2016), Vanishing Vernacular: Western Landmarks (2018) and most recently, American Motel Signs, 1980 to 2018 (2020).

Steve Fitch has always been an educator, he taught photography for forty-two years at the University of Colorado, Boulder; The University of Texas, San Antonio; Princeton University and Santa Fe University of Art and Design. Fitch has received four National Endowment of the Arts Fellowships as well as the Eliot Porter Fellowship. Retired from teaching but not from image making, Steve Fitch lives off the grid with his wife and two dogs in a passive solar adobe house they constructed themselves in rural Santa Fe County, New Mexico.

Additional resources

- Flickr – Installation images

- www.joanmyers.com – Joan’s official website

- www.stevefitch.com – Steve’s official website