Juror: Kathryn Hixon

Curator: Hank T. Foreman

Curator’s statement

On behalf of the Catherine J. Smith Gallery, An Appalachian Summer Festival, and Appalachian State University, it is a great pleasure to present the 14th Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Competition and Exhibition. Each new year brings us ten works to excite, stimulate, entertain, and challenge us. Some works, while completely contemporary in approach, possess the ability to speak in a language that emotionally and aesthetically link us to sculptured traditions with which we are familiar. Other works, while drawing on these same traditions, present themselves in ways that at first seem like a different language entirely. It is this range of investigation and creation that make this exhibition exciting, stimulating, entertaining, and challenging.

Every year the Rosen Juror is faced with hundreds of works, and it is the juror’s task to narrow this number to ten. These ten works will reflect the juror’s interpretation of what is going on in the world of contemporary sculpture, and their belief that the ten works chosen reflect at the highest possible level the dynamic, intelligent investigation of experiencing art in three-dimensionality. It speaks highly for this competition, the Festival, the University, the community, and the patrons that sculptors have a place where the diversity of research is understood to be important for artists and viewers. This year we have ten very different approaches to sculpture and each work has different insights to share.

It is impossible in this space for me to do justice to all the concepts and methods involved with this year’s sculptures. However, I would like to briefly share some core thoughts about the ten works selected. These thoughts are only meant to provide impetus for your own investigation and I am sure that you will learn much about the works and even yourself.

After viewing all of these works, and participating in a dialogue with each piece, we are drawn to even larger questions. What is contemporary sculpture? Are artists approaching the medium of sculpture from varied points? If so, what seem to be some predominant concerns? What role does the artist expect the viewer to play in experiencing the work? What kinds of presentations seem to immediately “make sense?” What works challenge your concept of sculpture? What biases do you bring to the dialogue?

These are important, challenging, and interesting questions. Questions that a competition and exhibition like the Rosen hope to inspire. We hope that you enjoy your experience with these ten new works and we invite you to live and dialogue with them throughout the next year. I congratulate the ten artists included in this year’s exhibit, the juror, Doris and Martin Rosen, and Appalachian State University for providing us with the opportunity to learn about contemporary sculpture and ourselves.

Hank T. Foreman

Director & Chief Curator

Turchin Center for the Visual Arts

Juror’s statement

As a way to share my experience as juror of the Rosen Sculpture Competition at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, I offer the following travelogue: I had never been to this part of the country before, and took the opportunity as a chance to explore the surrounding landscape. Hank had suggested I visit Linville Falls, so I got a map and some directions and headed off. Following the signs off of 105, I found the parking lot, and joined some scattered tourists to several overlooks from which we gazed on the effects of time and gravity that had produced so spectacular a waterfall. Scrambling up to get the best view I noticed some visitors, tiny from my vantage point, down at the bottom of the gorge. I wanted to experience the view from down below. I drove in the direction I thought I should go, got lost, turned around, went back past the parking lot to a ranger hut. Though directions were offered as to how to get to the bottom of the gorge, another possibility was suggested: a five-mile ride up the ridge to get an even more spectacular view: this time of the entire Linville Gorge. I drove up the winding, increasingly precarious roads up to the described spot: and was not disappointed. From Wiseman’s View, I scanned the great wilderness, musing on the vastness of geologic time, on the brilliance of the mountain wildflowers, and even on a practical bent that seems very American: to let the wilderness that is the most resistant to human cultivation remain so, then to shift our relationship with nature from mastery to calm appreciation: from exploitation to tourism.

I had recently been to the 99th floor of the Sears Tower in Chicago, where I live, and had luxuriated in the amazing view from up there, of the grids of city lights glittering into infinity. But my knowledge of the streets below, of negotiating the microcosm of urban neighborhoods with their specific unique trials and tribulations, are what made that generalizing view so extraordinary. So I still wanted to get to the bottom of Linville Gorge.

I followed the ranger’s directions, found the Blue Ridge Parkway (and instantly understood both its historical and contemporary uniqueness), followed the signs to the parking lot and ranger station. I hiked along what seemed somehow familiar trails, then backtracked, looked at the user-friendly park map, and found the way down to the river. This plunge down the gorge was all specifics, of negotiating twisted roots and dodging branches. There were no great vistas here, just dirt and trees and an occasional slithering snake. When I finally reached the river no one was around, and I felt relieved to stick my feet into the rushing water which reflected the sun in glittering arrays. Then I looked up to the overlook points and saw my fellow tourists, tiny from my vantage point far below.

I realized, of course, that from my first stop, if I had just explored in another direction, interpreting the park signs in different ways, I could have found the way down into the gorge in a few minutes.

Instead, I made a wide detour, intersected with institutional proclivities and personal territories, and ended up with a meandering but highly satisfying set of experiences. I had my own goals, waylaid by others’ wishes, then set again on my own desires.

My misshapen hiking trip is like sculpture, which is a three dimensional expression of subjective experience. Sculpture meanders through the world with its own agenda, but gets sidetracked with unpredictable experiences that temper its form. It offers grand vistas of sweeping gesture, or it stands separately, a lone monolith gathering up into own stalwart physicality or hunkering down to become one with its earthbound nature. Sculpture is form and composition, like rocks; and it is structure, like geology. In its assertive presence, it sometimes seems timeless. But it also embodies a social history, as do the highways and ranger stations, of humans toiling against the elements to shape a way for themselves through a natural chaos. Sculpture can be antagonistic, a way to raise up individual expression in the face of overwhelming conformity, and it can be an acquiescence, a succumbing to organic forces that will always triumph over small petty concerns.

Sculpture is a tool. It is practical, like a parking garage or a picnic table, offering a place in which to sit, converse, and meditate. Sculpture is a desire to belong, to conform, to represent its environment even if it is through opposition, adding unnatural details to point out the regular and the everyday. And sculpture can be both detail and shelter, a graceful eye-pleasing ornament or a comforting warm place of safety. Occupying a space between architecture – representing our need to separate and protect ourselves from the unknown – and nature – the unknown with which we are always trying to reconcile – sculpture offers a creative potential through which we can understand our ever-shifting position in the world.

I thank all of the entrants in the Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Competition for sharing their sculptural experiences with me, and Martin and Doris Rosen for making this experience possible. Seeing the ten finalists’ works on site on the grounds of Appalachian State University was a revelation of sculptural possibility, and a testament to the continued potential of the competition. Hank Foreman is to be continually lauded for his commitment to sculptural risk-taking. I especially thank Amy Gerhauser for giving a place, around a tree, in which I could contemplate my experience of ASU and the Linville Gorge.

-Kathryn Hixon

Amy Gerhauser, Sheltering Spiral II. 2000 / 14th Rosen Sculpture Competition Winner.

Sculptures

-

Sheltering Spiral II1st Place

Sheltering Spiral II

Amy Gerhauser

Norfolk, Virginia

Steel, found limbs, fabric and shellac. Site specific.

Artist statement

My work is theme-driven and addresses ideas about transience, transformation, and journeys; most recently themes have developed through cocoon-like or architectural forms that combine a paper or fabric membrane over steel and wood armatures. The specific nature of each sculpture evolves through the building process, influenced by the use of materials found nearby.

Sheltering Spiral II was constructed on site using steel, found tree branches, twine, muslin, and shellac. This sculpture, like most of my work, is temporary; the fabric will weather, tear, and discolor, and the steel will continue to rust. The gradual deterioration of the sculpture, like the shedding of skin, is central to its content. Sheltering Spiral II is a small private space designed to be entered; claustrophobic or comforting, solitary, light and ephemeral.

Curator’s comments

The second site-specific work, this sculpture interacts with the natural environment, but also creates a new structured space within that environment. How does your experience of the interior space shape your interpretation of this work? How would the use of different materials have altered this work and your experience?

FS.949

Rudy Rudisill

Gastonia, North Carolina

Galvanized steel

Artist statement

My work tends to be architectural in appearance and deals with the relationship between interior and exterior space. In some cases it makes references to the human body and male-female relationships. Sometimes I deal with the issues of ascension and/or exclusion. On the other hand, sometimes I deal with architectural forms for the sheer pleasure of dealing with the geometry of the roof line and its relationship with vertical planes.

I make drawings. The images come from memory, dreams, and from the act of drawing – manipulation of elements, abstraction and reducing details in a quest for the essential. I’ve always been interested in buildings of all sorts. Farm buildings, especially the towering grain elevators, that I’ve seen while traveling in the mid-west have had a pretty significant influence on my work. Lately I’ve come to realize that the view outside my studio window holds images that appear quite frequently in my sculpture as well.

Technically, most of what I do is sheet metal fabrication. I cut, form and fasten together sheets of metal. I use galvanized steel (steel with a coating of zinc) because it can be treated chemically to take on a matte finish with an almost instant look of age. Left untreated it has a bright silver finish and is rust resistant. Galvanized steel is tougher, as well as harder to cut and form, than mild steel of a similar thickness and is generally cleaner since it does not have to be coated with oil to prevent rust during handling.

It seems like I grew up in the metal shop. As a small boy I remember being told that I must wear shoes to go in the shop. Later, when I was tall enough to see what was happening on the workbench, I began to watch and eventually help my father make all sorts of metal objects – ductwork, chimney caps, hoods for the local cafes, parts for farm implements – things that, back then, were not available ready made. The idea that three-dimensional objects could be made from flat sheets of metal struck a chord with me. Put a sheet of metal on the workbench; measure, mark, make a few notches, cut out a piece, carry it over to the bending break and form it. This process still has a magical quality for me.

About the artist

Born in Gastonia, North Carolina, Rudisill conjures a building lost and abandoned, excavating it from memory. The illusion of change arises via galvanized steel and copper brushed with acid, yielding a corrosive effect. The work is simultaneously contemporary and traditional, industrial and pastoral as Rudisill explores the relationship of physical elements to their symbolic implications. By bringing together various textures and architectonic forms, personal, cultural, and historical elements bind together in and homage to the changing landscape. Each anthropomorphic piece carries with it a narrative and a particular relationship—sometimes familial, other times structural. A working artist for over 25 years, Mr. Rudisill’s fabricated sheet metal sculpture has won international awards and can be found in public, corporate and private collections in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Curator’s comments

This work, through its design and materials, references architecture and industrial function. How does our personal catalogue of experiences affect the way we view sculpture? What images from your past are evoked by this work?

Hammered

Matthew Harbstreit

Manhattan, Kansas

Steel and concrete

Artist statement

This piece entitled Hammered was built in reaction to an experience that I had late one night with three drunks. I found out later that they were neighbors of mine. Needless to say, it wasn’t a pleasant experience. I always try to keep my mind open and learn whenever I can. We all draw on our “Life” experiences. They help to shape the people we are and I feel honored to share one of my life experiences with you. I hope my use of line and shape and my choice of materials relays the message that there are ways, other than violence, to deal with everyday problems. Using one’s own intelligence and understanding can help to make this a better world.

Curator’s comments

The materials and design of this work alludes to an industrial purpose. How did the artist achieve this? Like the last work, what role does scale play in your interpretation?

King Fit

Shaun Cassidy

Rock Hill, South Carolina

Painted steel

Comments

Both the featured consumer items of Pop Art, and the bizarre juxtapositions characteristic of Surrealism, inform the giant steel sculptures of Shaun Cassidy. Cassidy explores and intensifies the psychological resonances of everyday objects, especially furniture, appliances, machines, and musical instruments. He does this by divorcing them from their original contexts, changing their scale, mutating them into one another, and unifying them with a consistent medium and surface color. His sculptures are both awkward and elegant, and often filled with a humor that arises from delighted surprise. Viewers are amazed by his weird transmorgrifications, and are equally disquieted by finding things of the indoor realm uncharacteristically outdoors.

Nick Capasso, Associate Curator

DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park

Lincoln, Massachusetts

Curator’s comments

Upon first glance, this work has a monolithic appearance. However, upon closer inspection the individual elements make their presence known. What effect does the paint application have on your experience of this work? What stories do the appliances evoke?

Listening Benches

Nitin Jayaswal

Gainesville, Florida

Cast concrete

Part of the Permanent Collection

Artist statement

The Listening Benches are investigations that demonstrate how the particular experience and function of one object can be implicated, documented, and constructed into another experience, function, and object. Architecture is a theoretical discipline based on auctoritas, that is, the authority of architects who obtain their authority by implementing acts of demonstration. The theory of architecture is established through demonstrations. Marco Frascari, Monsters of Architecture.

A studio or workshop is distinct from other spaces. It must be open, durable, ventilated, flexible, and accessible. It is usually a leased, rented, or borrowed space for the fiction of one or more persons. The artist is dependent on its capacity for production and their occupation of it involves particular focused activities such as desire, imagination, invention, and certain methods of working. This combination of work and thought is an important part of the studio’s space and its various types of leaning, tilting, stacking, and storing. The studio space contains various materials, equipment, and excesses of its own production. The space is alchemic, exaggerated and so while it’s not surprising to see hundreds of cars drive away from an assembly plant, neither is it surprising to see a four ton bronze emerge from a studio to be loaded for installation to a site.

There are particular adaptations to the studio’s own excesses. The floor is hard, smooth and its space usually remains open for maneuverability and movement. The use, removal, and storage of molds, armatures, platforms, models, tools, machinery, and raw materials which together usually add up to be greater than any finished object, all need to be movable or unfixed. An artist during the course of work is accustomed to having access to wheeled dollies. Likewise, there is one that is preferred and its capacities become spatial to its use and user. A cadence or relationship is made through the dolly’s use and function.

The Listening Benches were generated from certain movements of the Studio dolly which I made for use in my studio. The Studio dolly is a site-specific object conceptually relating to its user, the artist, to their context, the studio, a space which is open and flexible. The dolly was built with a pair of offset wheels that produce a swagger which in turn was recorded both vertically and horizontally. These measured drawings were constructed into a set of formworks and filled with cement. This topography of the dolly became inscribed upon a new surface which defines by its own form, the clarity and vagueness required for seated reflection. The placement of the Listening Benches provides a specific relationship between their siting in this particular public space and the adjacent fine arts building which contains studios and dollies.

Curator’s comments

These benches, created from the artist’s study of a hand cart’s movement, undulate and curve in a complex way. However, the overall appearance is subtle and simple. How does the functionality of this work affect your interpretation? What about the design makes you feel invited to participate?

LVOB

Jean-Paul Bourdier

Berkley, California

Paint pigments and earth

Artist statement

The process of creating usually begins with a vibration. What never fails to move me in the contrasting landscapes of sand, salt, snow, ice or rocks is the immense and yet very definite richness that Nature offers the one who can profoundly tune in with her, whether on the large or on the small, even minute scale. Most exciting in creating is the combination of elements such as: the simplicity of primal forms and materials; the diversity and specificity of textures available, and the range of possibilities they suggest; the mystery play of light whose movements, seconds by seconds, shift our perception of things and accentuate the drama of the exalted moment – the artistically accurate Moment to be captured on photograph. In other words, what constitutes a constant source of inspiration for me is the infinitely sensual universe in which ice and earth are the primordial clay, the very elements of cosmic integration in the process of sculpting with light (or color) and dissolving with time.

Sand, rocks, ice and powdered pigments are here not used as “instruments” to express form. They are materials that dictate the artist’s gesture. For example, grains of sand perform through accumulation and gravity; they are pulled towards the earth. Whereas ice performs through the cutting, melting, and welding of sections. To each material corresponds a different gesture, from which an instant of form is born with its singular atmosphere of concreteness and abstraction. Light, as choreography that retraces the movements of the hand and body, partakes in the vitally perishable relationship of the work with time of the day and the changes of nature.

In this aesthetic of disappearance and of the immediate, a dialogue is also created between photography and sculpture. The framing of each artistic event is here deliberately rational. The “unnatural” rectangular delimitation of the photograph is not taken for granted, but is itself a compositional element of the framed event. Emphasizing the two-dimensionality of the image and doing away with scale, and hence avoiding both the illusion of three-dimensional realism and the sentimental location of man in nature, the framing acknowledges its mediating activity and what it offers is no more no less than an image of the Moment in which the creation takes its (artistically accurate) shape before returning to formlessness.

Curator’s comments

This work is one of two site-specific installations this year. Immediately, one recognizes that the artist is using the physical environment and the placement of the circle drawings to explore three-dimensionality. How does an artist’s use of ephemeral or disintegrating materials relate to your concepts about sculpture? How does the scale of the work affect your experience?

My Father’s Lintel

J. Paul Sires

Charlotte, North Carolina

Terracotta and granite

Artist statement

I believe in “Relative Perspective.” How we view objects, and situations is determined by who, what, and where the viewer comes from and brings to a situation or a work of art. I also believe that all objects project a variety of doorways to allow viewers to interact with a work. As an artist I am constantly amazed at the power of simple forms and objects and the truly mnemonic and creative energy they release.

My work over the past several years has become simplified and hopefully more poetic, spiritual, and contemplative. My desire is to create works which convey a “state of being” and use a poetry of materials, forms, and simple marks. I view my work as traditional sculpture. That is, I am involved in creating 3-dimensional objects out of materials that have a true sense of permanence and endurance as compared with the human life span. I am interested in materials that have a classical/inherent beauty and quality. I primarily work with material such as stone, granite, terracotta, and some bronze.

Curator’s comments

Created of granite and terracotta, this sculpture makes reference to architecture. How does the title of the work affect your interpretation? How do you relate to the artist’s use of an architectural reference?

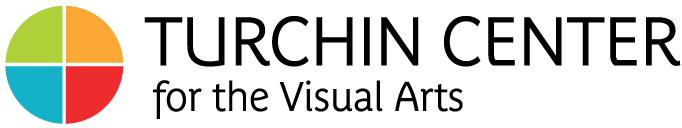

Poriferaserrata

Don Creech

Edisto Beach, South Carolina

Steel and concrete

Artist statement

My goal for both the artist and the viewer is to create a visual phenomenon that will create a “resonant frequency.” I believe that is achieved when both the old and new parts of our accreted brains respond to certain sensory events to create that unique emotion we call art.

In my particular case I use organic forms. No known organisms are portrayed, but rather plausible ones are merely alluded to.

Curator’s comments

This work is based upon the artist’s study of regional biology. How has the artist’s use of material and his methods alluded to the biological nature of his investigation? What role does scale play in your interpretation?

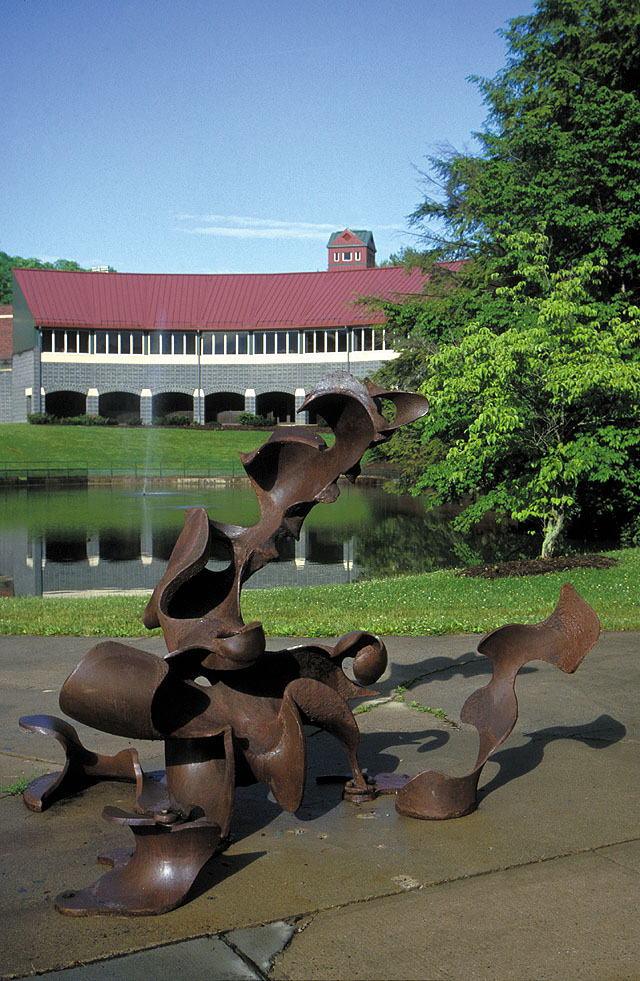

Purple Spire

Mike Callahan

Greensboro, North Carolina

Painted fiberglass and steel

Artist statement

I build things!! I just have always liked to build things. It must be how I know that I am alive and thinking is to figure out how to make something that is living in my mind. By the time I received my BA I was in my thirties and had been making a living from my art for years. I was supporting my family from my work and living in the first house that I designed and built with my hands.

Over the years I have built two homes and renovated four. I have built four other buildings as studios where I do my work. I like the scale, big rooms, high ceilings. I move boulders that strain my back and scar my hands. I throw delicate bowls with a lip so smooth and sensual that drinking tea from them is like a kiss.

Perhaps it is due to the years that I worked at my wheel, watching clay grow into forms of grace. Perhaps it is that I have chosen to build my home in the woods, where giant oaks are my moving, growing, powerful, whispering companions. Whatever the reasons my eyes have turned from that which I turn in my hand to that which I look against the sky. Looking to where the lace of winter hard woods is intersected by the graceful path of birds on the wing. Forms, lines and paths provide the foreground for mercurial clouds to pass on a field of blue.

I want my work to ascend amongst the trees. I want the grace of my sensual bowl, the curve of the bird’s wing, to stand against the sky.

“Spires” rise amongst the oaks at my studio. The oldest are, in sections, of stoneware, hard but fragile. Gray spires, up the hill by the twisted pin oak, are of steel and cement strong, permanent but so heavy that a crane is required to right them. Bright color, spring flower, fiberglass and steel, light and strong, now spring from the boulder punctuated red clay where I labor. Spires of an infinite palette now can rise with the grace of blades of grass, in the meadow, in the woods, in the city.

These forms are the work of the hand of man, the mind of man, the aspirations, reaching up. They are the dance, a contrast to the stiff line of brick, glass, and iron. I like building them.

Curator’s comments

Nestled in the Broyhill Music Center Courtyard, the vibrant purple of this sculpture pulls you into the space. How does color affect a viewer’s experience? This work was intentionally sited in a very architectural space. What is the relationship between the sculpture and the surrounding architecture?

Reclining Figure

Bill Anderson

North Wales, Pennsylvania

Steel

Artist statement

Extracted abstracts: sculpture from deep within the id. The sculpture at the predawn of history & why humanity is/is not obsolete without/with its objects of art. Since found-objects-of-concept and found processes to form new-objects-of-concept generate unruly excursions for neuron-synapse vessels, observed strings of creative juice initiates enlightenment of no conceivable purpose. “What is that” is not a question: rather, ’tis conceptus.

Signed: bill-to-planet-earth

Curator’s comments

Notice how thoroughly integrated this sculpture is with the natural environment. What does that say about the artists concept of outdoor sculpture? Would the work affect you differently if the sculpture were made of different material?

About the curator

Hank Foreman serves as Assistant Vice Chancellor of Arts and Cultural Affairs as well as Director and Chief Curator of the Turchin Center for the Visual Arts for Appalachian State University. He obtained his M.A. in Art Education from Appalachian, having completed undergraduate studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, with a concentration in Painting and Sculpture. His duties include the administrative responsibilities for An Appalachian Summer Festival, the Performing Arts Series, Farthing Auditorium and the Turchin Center for the Visual Arts.

During his tenure at Appalachian State, Foreman has taken part in the organization of numerous exhibitions, including the associated lectures, symposia, and publications. He has worked closely with the university’s Department of Art, and a wide variety of other campus and community groups, to make gallery resources available to all. One of his earliest exhibitions at Appalachian, Views From Ground Level: Art and Ecology in the Late Nineties, brought internationally acclaimed artists, historians, and critics to the campus and received national attention.

Foreman is also an exhibiting studio artist, and participates in regional and national conferences as a presenter and panelist.

A Special Thanks from the Curator

On behalf of An Appalachian Summer Festival, the Office of Cultural Affairs, and the Catherine J. Smith Gallery, I wish to thank all of the artist who participated in this year’s competition and congratulate those chosen for the exhibition. Each year the Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Competition and Exhibition is made possible by the generous support of Martin and Doris Rosen. The Rosens are tireless supporters of the arts, and over the years have given so much of themselves to ensure that the arts became a more integral part of our community. Their excitement and dedication serve as both inspiration and role model. I would like to thank our juror, Kathryn Hixson, for her dedication and professionalism during the completion of her difficult task. I wish to thank my colleagues in the Office of Cultural Affairs, my colleagues in the Art Department, and the students who participated in the installations. Special thanks to our designer – Michael Fanizza, photographer – Troy Tuttle, Assistant to the Gallery Director – Kim Johnson, the folks at Boone Crane, and our interns Donna Greer and Sarah Parker. A heartfelt thanks to Jim Bryan – Grounds Superintendent, and to Evan Rowe – Safety Officer. We also extend our thanks to the entire Grounds Department of the Appalachian State University Physical Plant. Their cooperation and expertise continues to make our campus a beautiful venue for outdoor sculpture.

Hank T. Foreman, Director & Curator

Catherine J. Smith Gallery