Juror: Jackie Brookner

Curator: Hank T. Foreman

For eleven years now, the Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Competition and Exhibition has provided the Appalachian State University family, residents of the regions, and visitors to Northwestern North Carolina with an invaluable experience: the opportunity to explore contemporary sculpture in a setting which facilitates the development of their personal relationship with art. With each passing year, the Rosen program has grown in professional stature, and has become an increasingly integral part of the Appalachian State University community. This exciting growth and development owes much to those whose vision shaped a path for the future.

Martin and Doris Rosen are among those visionaries, and I would like to take this opportunity to extend my sincerest gratitude for their support. A generous annual gift from Martin and Doris Rosen makes the sculpture competition and exhibition possible. However, my gratitude is extended especially for their generous gift of spirit; a spirit which allows them to be supportive of a diverse group of jurors, artists and artworks. The competition which bears their name can often include artists whose ideas, from context to construction, might not align with their own views of art. This stamina and faith illustrates a strong respect for artists and art. I thank them for their vision and their example.

On behalf of An Appalachian Summer Festival, the Office of Cultural Affairs, and the Catherine J. Smith Gallery, I wish to thank all of the artists who participated in this year’s competition and congratulate those chosen for the exhibition. I would also like to thank our juror, Jackie Brookner, for facing the challenge of choosing ten works out of such a diverse and strong group. Indeed, it is the juror whose holistic vision of the work shapes the character of each exhibition.

Hank Foreman, Curator

Juror’s statement

In today’s world with its instant global communication, its surfeit of moving images, and fast paced MTV cuts, sculpture seems a sluggish, even stubborn art form. In its stillness, not quite of this time.

The task of jurying the Eleventh Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Exhibition has given me the opportunity to ask again what sculpture has to offer us today, what can it mean to its makers and to its audiences, and to ask if indeed sculpture still has possibilities that it uniquely can fulfill.

Most obviously, sculpture is physical. It exists in the same place that we humans do and like us, must obey the laws of gravity. In this way – it is grounded. Why is this important, or even desirable when so many of us today seem to prefer illusion and the ungrounded, the possibility of tickling our brains into believing in the ungravitiational world of virtual reality where we can move about at will, through spaces and even solids, unimpeded by the limitations of our physical bodies?

Sculpture endures these limitations and beings us back to our bodies. It celebrates the spaces that surround us and the spaces within us. It reminds us that we stand on the ground, that we walk with our legs, that we feel touch through our skin, that we track constant shifts of light with our eyes, and that with every breath and step our visual field changes, however slightly. With attention, we can feel how sculpture works on us through our own kinesthetic sense – how small muscular movements empathetically respond to what we see, creating feelings of tension, relaxation, compression, expansion, sadness and joy. Whether abstract or carrying an image, sculpture communicates to us primarily through the kinesthetic sense. Be it the texture or density of the materials, the weightlessness of lines or the heaves of masses, a soft quiet play of light or quickened syncopated rhythms – these awaken empathic responses in our bodies and help us create meaning from what we perceive. In stimulating our bodies, sculpture stimulates our souls.

While it shares many of these qualities with dance, sculpture’s stillness allows for quiet, out of time, contemplation. Slow paced, perhaps archaic – sculpture is needed today, perhaps more than ever. In evidence, an anecdote – a telephone salesman called offering me a free service – no dial calling – where you need only speak the name of the person you wish to call and the call with be connected. I told him no thank you, I like dialing, and fear for our fingers – that they may one day atrophy from lack of use.

Martin and Doris Rosen are to be gratefully thanked for creating the opportunity for so many sculptors to exhibit their work and for so many people to experience this work in the spacious setting of Appalachian State University.

– Jackie Brookner

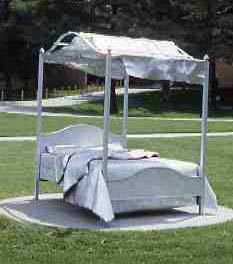

R. F Buckley, Sleep that knits up the raveled sleave of care. 1997 / 11th Rosen Sculpture Competition Winner.

Sculptures

Sleep that knits up the raveled sleave of care

R.F. Buckley

Miami, Florida

Forged aluminum. 9′ x 6′ 6″ x 9′ 4″

Artist statement

From an earlier series of fluid forms, the meandering calligraphic lines inherent to a draped cloth has established itself in my work as an abstracted common denominator between elemental natural forms – most especially the landscape and configurations of the human body. Where the previous work produces a hybrid form taken from a variety of references linked by similarity, the recent work confronts the viewer with a realistic representation of the recurring flowing profile. In Sleep that knits up the raveled sleave of care, the forged aluminum undulates to suggest the human forms etched, worn and indented into a bed that has just been slept in.

African Crucifix

Ken Smith

Myrtle Beach, South Carolina

Bronze. 6′ x 2′

Artist statement

I am interested in creating rhythms of light and dark in my pieces and I strive to couple these dynamic rhythms with stimulating and sometimes disturbing themes. I want my pieces to invite the outstretched hand to enhance the experience the viewer shares with my art. My concept for this piece evolved as a simple representation of countries that have suffered famine in Africa, this was not my intent. I am presenting the paradox of the death of civilizations at the very birthplace of civilization, the cradle of mankind, Africa. The baby represents mankind and the mother is the mother of all, Earth. The globe at the female’s feet symbolizes the schism between the haves and have nots. This was added after the piece was well under way. The color of the life size piece was also important in my mind. I chose a warm brownish gray, the color of malnutrition and the third world.

Bodacious

Teresa Young

Oxford, Ohio

Welded steel. 6′ x 2′ 2″ x 2′ 2″

Artist statement

I have always been a maker of objects. My tenacious curiosity and imagination, and the love of making are my main motivations for creating. My work is not limited to a single interpretation, rather; it reflects the human experience. I believe we are reflected in the objects with which we surround ourselves, and the significance of objects is our experience of them.

When I violate the usual scale, material, or function of a particular object, to emphasize what I am seeing sculpturally, that object begins to offer nuances of idiosyncratic meaning. By focusing on giving the everyday of archetypal object a greater sculptural presence, I celebrate our experience of objects, arouse curiosity, and spotlight the act of making.

Rusted sheet steel is raw, unfinished, straightforward, and without pretense. Cutting it into many eccentric shapes transforms the seemingly dull and lifeless metal into a material that has a wonderful patina and is richly textured. Welding piece by piece allows me to work spontaneously, choosing each piece and tacking it into place, one after another; documenting a ritualistic investigation of form and making. I think of it as sewing in steel. My fabric is steel. My needle and thread are the tack weld.

Working this way also mirrors the way in which we navigate life. We patch our experiences together to form who we are in the world. My work confronts us with our relentless imperfections yet it reflects the beauty of those imperfections. It celebrates the universal journey of life, its peculiarities, and our preoccupation with objects.

Estelle

Matthew S. Newman

New Braintree, Massachusetts

White oak. 12′ x 12′ x 3′

Artist statement

Twenty one years in the sawmill woodshop, the challenge is strong as ever. Start with raw materials (logs) harvested locally, and process all the wooden parts from scratch. Never hold back, you can’t let go. Maintain control and go for broke; there is very little that means as much.

Falline Flora

Don Creech

Edisto Beach, South Carolina

Steel. 7′ 9″ x 4′ 6″ x 4′ 11″

Artist statement

My works are a way of trying to make nonverbal connections within the mind of the artist and then, hopefully, the viewer. In my pieces connections are formed through allusions to organic structures or systems … not specific organic forms. The viewer who is able to respond to particular visual material experiences a primary experience differing from the secondary, or, symbolic type provided by the verbal sphere.

Evolution has added a highly analytic capacity to our repertoire. It’s a newer part of us. I recognize that symbolic thinking will follow and complement the initial intuitive phase.

Glissand

Jerry Monteith

Cobden, Illinois

Steel and wood. 3′ x 9′ x 8′

Artist statement

I have a fascination with the physicality of sculpture. Current large scale works allow the viewer to enter them, and to feel the effects of their intervention, as the piece rocks back and forth. My appreciation of the massive or volumetric form acknowledges the legacy of certain Minimalist works, which pair grand scale with simple form. Regardless of the bodily response one has to this work, the practitioners of this thoroughbred sculpture were criticised for closing out the viewer and providing a paucity of expression. My desire is to open up the relationship between the viewer and work, physically describing the context – or place – of the viewer/participant in the process. A person’s interaction with a given work reduces the distance between viewer and artwork.

Glissand was one of the first works which I made, fully intending that people should sit on it. Its steps infer this. Moreover, they make it physically possible. The opposite end is tapered, and refers to a boat form, a vehicle for transport. In a nutshell, this work and many like it provide for the viewer to become actively involved in the art process. The art is the form plus the experience of interaction.

Kayak

Thomas McDonald

Berwyn, Illinois

Steel. 10′ x 1′ 10″ x 1′ 8″

Artist statement

Although I consider my Artwork to be open for interpretation, it is a reflection of my life’s journey and a search for my true heritage. Not just a physical journey but an intellectual, emotional and spiritual journey of understanding; a life long voyage of trying to understand who I am, where I come from and what my role is in our diverse society. The sculptures I produce appear to be functional objects for the traveler. Based on the concept of the Swiss Army Knife, these journey objects look as if they were prepared on the spur of the moment, conveying the message that one should begin their own journey of understanding as soon as possible. Through the use of materials (found objects) I believe the work to open a discussion about our society’s contemporary topics. The topics of class, gender and the environment in the post-industrial age. Perhaps they are a metaphoric look at Mankind’s constant effort to reinvent itself in order to survive peacefully, or a foreshadowing of the future if action is not taken now.

SNY 945 GA

J. Zac Ward

St Simmonds Island, Georgia

Steel and epoxy. 8′ 7″ x 5′ 2″ x 4′ 7″

Artist statement

My ideas of art and sculpture are more about how other people interact with the work. As a sculptor, I try to make work that contains a relevance in space. Form and scale are the dominant voice of my work, process only to influence the evolution of form and scale. Scale becomes a problem in terms of transportation, so I began experimenting with the idea of trailers as sculptures.

Presently, the trailer functions as the groundwork for new work. The first test run of this trailer was held in the parking lot of a Wal-mart. The run did not go so well. I had considered the possibility that something could go wrong, since the Air Force oxygen cart I retrieved from a junkyard had written on the side, “Do Not Exceed 20 mph.” At about 65 mph there was massive vibration. So at this moment the trailer is not realized to a desired quality in the technical sense; however, my plans are to travel with it in order to film a documentary of people’s reactions to these mobile, high-speed, “street legal” sculptures. The documentation of the viewer’s reactions and comments about my work will be needed research that enables me to pursue and develop new sculptural concepts. I have been inspired by people’s interest in learning more about my work; “what is this object … why are you doing it … why is it art?”

Throne for Marin Luther King Jr.

Ted Garner

Ayden, North Carolina

Steel and wood. 7′ x 18′ x 9′

Artist statement

Throne (For Martin Luther King) is intended to be a play area for children, a place for people to sit and relax, an attractive nuisance if you will; and most importantly, a prayer for cooperative coexistence. The form of the sculpture derives from a combination of thoughts, a bird of freedom, the American landscape and flag.

About the artist

Education: BFA, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, MO.

Two by Two

William Donnan

Franklinville, North Carolina

Reinforced cement. 14′ x 8′ x 9′

Artist statement

I am trying to reconcile contemporary man’s ambiguous attitude towards nature with the older impulse to worship nature.

Curator’s statement

It has often been proposed that the most important aspect of a gallery, visual art center, or museum is the experience of the actual art object or event – not a virtual experience, but rather a pilgrimage to the “real thing.” Walter Benjamin, in his essay entitled The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, laments the loss of visiting real works, in real spaces dedicated to them. Benjamin ponders the “aura” of an artwork and the contemplative nature of experiencing it firsthand.

In this age of virtual realities, virtual museums, and art on-line, Benjamin’s concern surrounding the quality of experiencing art through reproduction seems even more warranted. There are issues of control: who decides what images are reproduced and distributed? There are issues of context: who decides how the experience around the artwork is designed – therefore affecting the viewers psychological and intellectual experience? However, just as there are negative aspects of this technological development, there are also positive aspects of the same issues – the increased availability of artworks due to the reduction of economic, and geographic stumbling blocks leading this list.

For centuries the relationship between people and actual art has been controlled by the places that own the work. Now works from collections previously unreachable by large portions of the population are available on-line. So while the risk of control is still very real, is it more of an issue than the manner in which the original collections were developed and presented? Is the risk of control really that great in a communicative medium where anarchy and diversity underlie much of its operation? If the issues of control and context (while recognized as important concerns) are debatable, and do not offer the most serious limitations to the experience of “non-real” art, what does?

The immediate answer to this question is quite nebulous – the limitation is that you are not experiencing the “real thing.” This means that answers really lie in the reverse of our question of limitation; what does viewing actual artworks give us that other methods of viewing do not provide? In our case, more specifically, what does viewing outdoor sculpture in person give us that seeing it reproduced might not provide? An initial response would be the sheer physicality of the artwork and the site. While this sounds vague, it leads one to investigate the complex issues that merge to create the three dimensional work and site. Each work has its own shape, size, weight, materials, textures, colors, and the topographical and emotive qualities of its environment vary by site – these even vary by season, weather and time of day.

All of these obvious, but often overlooked, details merge together to provide us with a specific interpretation of a work at a specific time. Another feature of this physicality is the anthropomorphic and intellectual relationship which is developed, by degrees, as one moves around, and sometimes through, sculpture. The importance of this ritual can not be discounted. For it is in this activity that the contextual connections blend with the physical responses of the human body in relation to the work. It is this active occupation of the same space and time that offers an important foundation for relating to sculpture.

The Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Competition & Exhibition, by its design, adds additional layers to this personal experience. The works are made public by their placement in the landscape, and for one year they become part of the daily life of the University community. This affords people the unique opportunity to experience the work through changing environmental, psychological and intellectual periods. The relationship with the works, enabled through their accessibility, becomes deeper because it is viewed through the changing context of people’s lives

Appalachian State University is fortunate to participate in a program like the Rosen Outdoor Sculpture Competition & Exhibition. Over the years, it has enhanced the cultural climate of the University community, and offered students, faculty, staff, and visitors a unique opportunity to strengthen their personal relationship with art. It is extremely fitting that the host for this program is a university whose mission is to prepare people to meet their creative and intellectual potential. This exhibition invites participants to stretch these faculties as they relate the works to their lives and the world around them.

Hank T. Foreman

Director & Chief Curator

Turchin Center for the Visual Arts

About the curator

Hank Foreman serves as Assistant Vice Chancellor of Arts and Cultural Affairs as well as Director and Chief Curator of the Turchin Center for the Visual Arts for Appalachian State University. He obtained his M.A. in Art Education from Appalachian, having completed undergraduate studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, with a concentration in Painting and Sculpture. His duties include the administrative responsibilities for An Appalachian Summer Festival, the Performing Arts Series, Farthing Auditorium and the Turchin Center for the Visual Arts.

During his tenure at Appalachian State, Foreman has taken part in the organization of numerous exhibitions, including the associated lectures, symposia, and publications. He has worked closely with the university’s Department of Art, and a wide variety of other campus and community groups, to make gallery resources available to all. One of his earliest exhibitions at Appalachian, Views From Ground Level: Art and Ecology in the Late Nineties, brought internationally acclaimed artists, historians, and critics to the campus and received national attention.

Foreman is also an exhibiting studio artist, and participates in regional and national conferences as a presenter and panelist.

A Special Thanks from the Curator

I wish to thank my colleagues in the Office of Cultural Affairs; Perry Mixter, Director; Gil Morgenstern, Artistic Director for An Appalachian Summer; Sali Gill-Johnson, General Manger; Sara Heustess, Box Office Manager for Farthing Auditorium; Greg Williams, Technical Director for Farthing Auditorium; Jim Sigmon, Assistant Technical Director for Farthing Auditorium; Denise Weissberg, Director of Marketing and Public Relations; Elizabeth Loflin, Assistant Director of Marketing and Public Relations; Sandra Black, Fiscal Officer; and Allyson Duncan, Office Manager. I would also like to thank the Art Department faculty and staff; Dr. Clyde Robbins Assistant Vice-Chancellor for Physical Plant Operations; Larry Bordeaux, Director of Facility Support Services; Jim Bryan, Grounds Supervisor; and Dr. Evan Row, Safety Officer.

In closing, my thanks to the many who make this exhibition possible, including the Art 4012 – Exhibition Practicum students and Michael Fanizza for this excellent catalogue design. Also thanks to Michael Siede and Troy Tuttle of the Technology Department for their assistance with the photography. Thanks to Gallery Interns Leslie Snipes and Ryan Bumgarner for their contributions to the summer program. Special thanks to Kim McDade, Assistant to the Director for the Catherine J. Smith Gallery, for her dedication, contribution and friendship.

Hank T. Foreman